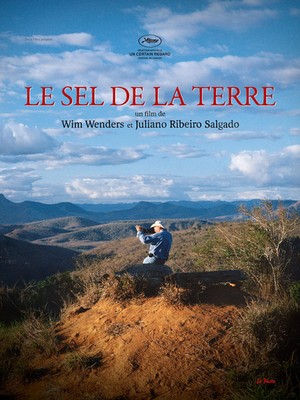

For the last 40 years, the photographer Sebastião Salgado has been travelling through the continents, in the footsteps of an

ever-changing humanity. He has witnessed some of the major events of our recent history; international conflicts, starvation and

exodus. He is now embarking on the discovery of pristine territories, of wild fauna and flora, and of grandiose landscapes as part

of a huge photographic project which is a tribute to the planet’s beauty.

Sebastião Salgado’s life and work are revealed to us by his son, Juliano, who went with him during his last travels, and by Wim

Wenders, himself a photographer

Interview with Wim Wenders:

For how long have you known Sebastião Salgado, and where you already struck by

his work before you met him ?

I have known Sebastião Salgado’s work for almost 25 years. I’d acquired two prints, a long time back, which really struck a chord with me and moved me. I framed them, and ever since, they have hung over my desk. Inspired by these photographs, I visited an exhibition called At Worksoon after that. Ever since then, I’ve been an unconditional admirer

of Sebastião’s work, even though I only met the artist in person five or six years ago.

What was the catalyst for the project SALT OF THE EARTH?

We met in his Paris offices. He took me on a visit round his studio, and I discoveredGenesis. This was an exciting new departure in his work, and as always, a project of huge scope that would unfold over a long period. I was fascinated by his involvement in his work and his determination. Then we met again, and we discovered we both love soccer, and we started talking about photography in general. One day, he asked me if I would be interested in accompanying him and his son Juliano on a journey without any precise goal on which they had started out, and for which they thought they needed another point of

view, that of an outsider.

Once you’d decided to co-direct the film with Juliano, Sebastião Salgado’s son, did you have to resolve any problems? The sheer volume of material, or the choice of

photographs? Beyond the sequences of Juliano filming his father, did you fall back on any other archive footage ?

The biggest problem was, in fact, the abundance of material. Juliano had already accompanied his father on several trips around the world. So there were hours and hours of documentary images. I’d planned to accompany Sebastião on at least two «missions» – in the great north of Siberia and in a balloon expedition over Namibia – but we had to

cancel that because I fell ill and so I couldn’t travel. So instead, I started to concentrate on his photographic work, and we recorded several interviews in Paris. But the more discovered his work, the more questions I had. And of course, I had access to a plethora of archive images.

Your presence in the film is warm and discreet: where and when did the interviews

Your presence in the film is warm and discreet: where and when did the interviews

with Sebastião Salgado take place? And what governed the choice of photographs

that you discuss together ?

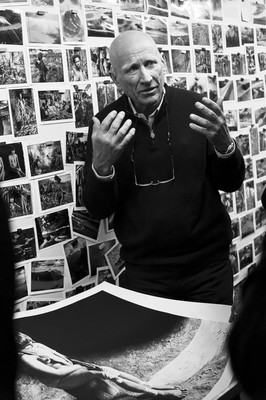

During the first interviews I appeared on camera. But as our conversations progressed, I

increasingly had the feeling I should «disappear», and that I should give the whole space

over to Sebastião and, above all, to the photographs. The work should be left to speak

for itself. So I had the idea of a directorial approach using a sort of dark room : Sebastião

was in front of a screen, looking at the photographs, whilst answering my questions about

them. So the camera was behind this screen, filming through his photographs – if that’s

how I can put it – thanks to a semi-transparent mirror, which meant that he was looking

at the same time at his photographs and the spectator. I thought it was the most intimate

setting for the audience to hear him express himself and at the same time discover his

work. We more or less cut out all the «traditional» interviews, of which only a few bits

remain. But they turned out to be a great preparatory stage for our sessions in the «dark

room». We chose the photographs together, and those choices were mainly dictated by the stories that Sebastião told me and which are in the film. We had hours and hours of

rushes at our disposal.

Did you encourage him to comment on his photographs by taking him back to the

time and place where they were taken? A Brazilian gold mine, famine in the Sahel,

the genocide in Rwanda, and so on. They are, for the most part, tragic images. Did

you ever find them «too beautiful», as some have reproached him ?

In the «dark room», we ran through Sebastião’s entire photographic oeuvre, more or less

in chronological order, for a good week. It was very difficult for him – and for us too

behind the camera – because some of the accounts and journeys are deeply disturbing,

and a few are genuinely chilling. Sebastião felt as if he was returning to these places and for us, these internal journeys «to the heart of darkness» were also overwhelming.

Sometimes we’d stop and I had to go out for a walk to get a bit of distance on what I’d just

seen and heard. As for the question of whether his photographs are too beautiful, or too

aestheticized, I totally disagree with those criticisms. When you photograph poverty and

suffering, you have to give a certain dignity to your subject, and avoid slipping into voyeurism. It’s not easy. It can only be achieved on condition that you develop a good rapport

with the people in front of the lens, and you really get inside their lives and their situation.

Very few photographers manage this. The majority of them arrive somewhere, fire off a

few photographs, and get out. Sebastião doesn’t work like that. He spends time with the

people he photographs to understand their situation, he lives with them, he sympathizes

with them, and he shares their lives as far as possible. And he feels empathy for them. He

does this job for the people, in order to give them a voice. Pictures snapped on the hoof

and photographed in a «documentary» style cannot convey the same things. The more

you find the right way to convey a situation in a convincing way, the closer you come to a

language which corresponds to what you’re illustrating and to the subject in front of you,

the more you make a real effort to obtain a «good photo», and the more you give nobility to

your subject and make it stand out. I think that Sebastião offered real dignity to all those

people who found themselves in front of his lens. His photographs aren’t about him, but

about all those people !

Did you work from a script for SALT OF THE EARTH, or was the film structured during

editing ?

I jotted the main outline of the film down on paper, and in the end, the «dark room» was

a conceptual device, but overall, as with any documentary, you have to try and shoot footage in the moment and not miss what’s happening in front of you because of some prior

decisions. That was specially the case when I went to Brazil and I filmed Sebastião and

Lélia (his wife) in Vitória, the city where they live, or inside the Instituto Terra: I had to let

myself be guided by the unexpected and be ready to shoot images on the spot. That’s the

other aspect of my contribution to this film: seeking to draw a link between the Salgados’

extraordinary “other life” and the photographic body of work. In a way, their ecological

commitment and their efforts to regenerate the tropical Atlantic Forest are, in my opinion,

as important as Sebastião’s photographs. As a result, I felt that we were making two documentaries at the same time, which we then had to edit into a single film.

The documentary offers the portrait of a man and brings to life his work. It also

offers a touching study of the father-son relationship. Was this dual undertaking

obvious from the start ?

Yes, from the outset, our film had several dimensions. The father-son relationship was

also clearly part of it from the start. It could have turned out to be a pitfall for the film, and

I think that the Salgados – father and son – were right to bring me in to avoid any risk of

that happening. But ultimately, it’s a very moving side of the film.

One of Salgado’s trademarks is his exclusive use of black-and-white. Does he explain this? In your own films (KINGS OF THE ROAD, the perception of our world by

the angels in WINGS OF DESIRE, THE STATE OF THINGS), you use it to great effect:

did this bring you closer ?

Yes, I can totally identify with his use of black-and-white. What’s more, the part of the

film that I filmed myself is also in black-and-white so that it sits better alongside his

photographs. At one point, we touched on this question in our interviews. But we ended

up not keeping that segment in the final edit. I felt that this aspect of his work could be

understood without needing any additional explanation.

Photography is something you have in common, since you yourself are known and

acknowledged as a photographer (and like Salgado, a long-standing fan of the Leica), and many of your movie characters (Philip Winter in ALICE IN THE CITIES, Tom

Ripley in THE AMERICAN FRIEND, or Travis in PARIS, TEXAS) have a link with photographs or photography. Did Salgado know your work the way you knew his ?

Sebastião took quite a lot of photographs while we were filming, including of the crew.

So I might have the honor of appearing in some of his photographs. But I don’t think he

knows my films as well as I know his photographs, which was the very reason behind me

making this film.

He was the subject of my film, and not the other way round.

Throughout the film, the presence, and the importance of his wife, Lélia Wanick

Salgado, in the life and work of Salgado is tangible. Did she play an active part in

the making of SALT OF THE EARTH ?

They’ve been working together for 50 years. Lélia brings a real energy to Sebastião, which

he needs for his works and his exhibitions, and they undertake his biggest photographic

projects together. As such, it was obvious that she too would appear at the heart of the

film. She’s an amazing woman, very strong, very forthright, honest and adorable. And very

funny. The Salgados do laugh a great deal !

The last part of the film is an unexpected journey, at the same time intimate and

powerfully ecological: the Salgado family’s return to the family ranch in Aimorés

in Brazil. A breathtaking landscape devastated by deforestation, and the Salgados’

incredible gamble – as we see, already starting to pay off – of replanting two million

trees. For Salgado the man and for the photographer of the most dramatic human

conflicts, could we speak of a happy ending ?

From the start, it seemed essential for us to take into consideration the fact the Salgados

have another life besides photography: their commitment to ecology. And from the outset,

I knew that I had to tell two stories at the same time. One could say that the reforestation

program they have set up in Brazil, and the near-miraculous results they have achieved,

concluded in a happy ending for Sebastião, after all the misery he has witnessed and the

depression into which he slipped when he came back from Rwanda for the last time, and

after the unbearable episodes that he has lived through. He not only dedicated his latest

monumental work,

Genesis, to nature, but one can also say that it is nature which allowed him to not lose his faith in mankind.