ARMAN – the exhibition – Museum Tinguely, Basel

“I maintain that the expression of rubbish, of objects, possesses an immediate intrinsic value, without the will of aesthetic compositions obliterating them and likening them to the colors on a palette; furthermore, I introduce the meaning of the global gesture unremittingly and remorselessly.“ ARMAN, 1960

From February 16 to May 15, 2011, Museum Tinguely will be showing a comprehensive survey of the work of the artist Arman (1928–2005). The exhibition is a cooperative project with Centre Pompidou in Paris, where it was presented last autumn to resounding acclaim, attracting a large number of visitors. With some 80 works contributed by leading museums and private collections, as well as a selection of films in large-scale projection, video recordings and documents, the second installment of the show in Basel features seven thematically arranged galleries providing a unique overview of the artist’s complete oeuvre from the early 1950s to his late work in the 1990s. Museum Tinguely is placing a special focus on Arman’s artistic pursuits in the 1960s and 70s. Five years after the artist’s death, this is the first major retrospective of his work ever to be held at a Swiss museum. Following projects on Yves Klein (1999), Daniel Spoerri (2001) and Niki de Saint Phalle (2003), Museum Tinguely is now proud to present the oeuvre of yet another member of the Nouveaux Réalistes.

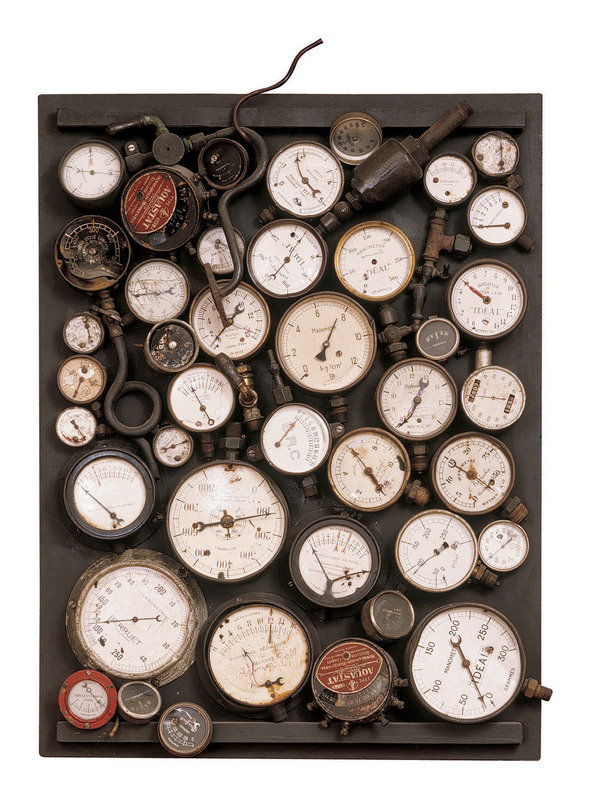

In the thematically organized show, important pieces have been selected to represent Arman’s major work groups, beginning with the Cachets and Allures d’Objets, abstract stamp and object prints on paper and canvas from the latter half of the1950s. At the center of the show are Arman’s provocative artistic reactions to the throwaway society, his famous Poubelles and Accumulations, in which he showcases discarded everyday goods and trash in glass and perspex boxes as objets d’art. Also on view are key works from the Coupes and Colères series, as well as from the Combustions and Inclusions, demonstrating the artist’s varied forms of engagement beginning in the 1960s with the theme of destruction, deconstruction and transformation of the accoutrements of our daily lives. Completing the exhibition are a selection of Accumulations Renault, assemblages of factory-new auto parts, some of them monumental, which were commissioned in the late 1960s by Renault, and finally, examples of Arman’s paintings and resin casts using paint tubes, in which he turned his attention from the late 1960s to the end of the 1990s to the medium of abstract painting, or Art Informel.

Today, Arman’s works from the 1960s and 70s seem startlingly topical; in particular his Accumulations, his Colères, involving the destruction of an object, and above all the Poubelles can be read as archaeological traces left behind by consumer society – astonishingly presaging how the throwaway lifestyle and the destruction of the planet would later become the most pressing concerns of our day.

Arman and Nouveau Réalisme

As a founding member of the Nouveaux Réalistes, Arman belonged to one of the most important artist groups of the postwar era, whose influence still persists today. The artists in Tinguely and Arman’s generation found themselves at a turning point, with modernist abstraction in painting having been declared dead. The Nouveau Réalisme manifesto (1960) took issue with Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism, art trends that dominated the Parisian art scene at the time. Pierre Restany noted in his text: “Easel painting has (…) served its term. Still sublime at times, it is approaching the end of a long monopoly.” Nouveau Réalisme proposed instead “the exciting adventure of the real seen for what it is.” This adventure, according to Restany, is only open to those who go about the world with a sociologically trained gaze, hoping that chance will rush in to assist, “whether it is the posting or the tearing down of a sign, the physical appearance of an object, the rubbish from a house or living room, the unleashing of mechanical affectivity, or the expanding of sensitivity beyond the limits of perception.”

Arman himself referred in 1960 to the object and the gesture as his primary media: “I maintain that the expression of rubbish, of objects, possesses an immediate intrinsic value, without the will of aesthetic compositions obliterating them and likening them to the colors on a palette; furthermore, I introduce the meaning of the global gesture unremittingly and remorselessly.”

Arman’s work in the 1950s

In Arman’s early work executed in the latter half of the 1950s (to which scant attention has been paid until now) the main artistic methods are already apparent that will set the tone for his entire career: the repetitive artistic gesture and the consistent use of everyday objects.

Interestingly enough, Arman came to the object by way of painting and concrete music, which he delved into intensely at the time. He was also influenced by the work of artists active in the 1920s such as Kurt Schwitters, Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman and Marcel Duchamp. In the mid-1950s he was close to Yves Klein, likewise from Nice and the inventor of International Klein Blue. During this period Arman conceived works on paper and canvas – the Cachets and Allures d’objets. In his Cachets he parts ways with the painting style of the École de Paris and uses rubber stamps to print all-over patterns on canvas in a kind of Écriture automatique. The Allures d’objets series, whose name comes from the music of Pierre Schaeffer, consists of abstract pictorial compositions formed by the accidental imprints and traces left behind by various objects dipped in paint and hurled at the canvas. Arman’s Cachets and Allures d’objets can be regarded as provocative reactions to the Informel painting and Abstract Expressionism that were all-pervasive at the time.

The significance of the object in Arman’s work

In the course of 20th-century art history, the everyday object was gradually endowed with its own aesthetic value, deemed worthy of exhibition in the museum – a development that is closely tied with the burgeoning of consumer society. Inspired mainly by Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the Readymade, Arman declared everyday objects his means of artistic expression. On the aesthetic level he was investigating here the differences and analogies between object and painting. In his Poubelles and Accumulations he piled up worn and discarded items, lending the transparent containers holding them poetic and frequently ambiguous titles. In 1960 he put on a revolutionary rubbish happening at the gallery of Iris Clert, filling it up to the ceiling with trash and objects of everyday use and calling the result Le Plein. In his Coupes and Colères Arman cut up, smashed and deconstructed the commonplace object. The items he chose (very often musical instruments) clearly connote the middle-class lifestyle. In common with the Accumulations, Arman staged here the aspect of presentation and display. Familiar objects arranged in repeating, louver-like patterns are rendered unrecognizable, offering the viewer a completely new way of seeing them.

In his Inclusions Arman encased objects in synthetic resin for posterity, or preserved them in a burnt state as a symbol of transience in the Combustions. What results are materialized evocations of arrested time in which the acts of creation, destruction and deconstruction converge. His work is hence a prime example of the destruction art of the 1960s, after the Dadaists perhaps the most radical break with artistic tradition in the 20th century. With his oeuvre Arman shows us the flip side of consumerism and the throwaway menta- lity. His work signaled a fundamental break with the commonly accepted artistic principles of imitation and representation of reality. And even today, when the boundaries of what we conceive of as art have broadened even further, we may find ourselves perplexed when confronted in museums with exhibits whose components we recognize from our own everyday world, or that of a bygone era: musical instruments, razors, high-heeled shoes, gas masks, antiquated Underwood typewriters, or radio tubes – Arman even presents the contents of trash cans ensconced in showcases as artworks.

Arman himself emphasized that his Accumulations were not meant primarily as a way of isolating a commonplace item from its usual functional context and hence charging it with new meaning. Instead, by piling up and multiplying objects, by reproducing one and the same object, he wanted to demonstrate that his artistic procedure correlated to the industrial working methods of “automation, assembly line work and series production of rejects,” which generate “geological strata and layers that reveal the cumulative force of reality.”

Arman’s artistic concepts and actions in the medium of film A special highlight of the exhibition is the large-format projection of films based on Arman’s ideas, including Objets animés (1959–1960, by Jacques Brissot) and Sanitation (1972, by Jean-Pierre Mirouze). The films enter into an intriguing dialogue with the pictures, reliefs and sculptures on display and form an important bracket bringing together the various themes addressed in the show.

Not only do the films make palpable for us Arman’s obsession with the object in all its inner coherence and logical consistency; they also shed light on the intellectual basis underlying the artist’s work. In Sanitation, a film about the consumer goods cycle in 1970s Manhattan, the camera follows the path of merchandise from shop window all the way to its disposal as trash, borne away in garbage trucks to a huge dump on Staten Island, with the Statue of Liberty visible in the distance. Here the exhibition visitor can get a sense of the timing and feel of the process, starting with the original purpose and function of things within our consumer society, then onward to objet trouvé and ending as finished artwork in the Poubelles and Ordures organiques series. A slow-motion clip from Arman’s early Colère action NBC Rage (1961), in which the artist chops up a contrabass atop a wooden board, reveals the ephemeral, explosive physical gesture behind his work. Another film shows Conscious Vandalism, a Colère exhibited at the John Gibson Gallery in New York in 1975 that was based on the furnishings of a middle-class apartment and the remains of which are on view in a special room in Basel. These spectacular actions have the effect of cathartic events within Arman’s oeuvre.

Catalogue

A richly illustrated monograph in German is being published to accompany the exhibition, with contributions by Jean-Michel Bouhours, Umberto Eco, Barbara Rose, Emmanuelle Ollier, Jaimey Hamilton, Renaud Bouchet, Marcelin Pleynet, Michel Giroud, Marion Guibert and Olivier Cinqualbre.

364 pages, 52 CHF/43 Euro

Tinguely Museum

Paul Sacher-Anlage 1- Basel

Opening hours: Thursday – Sunday 11 – 18 h (closed on Mondays)

Admission prices: Adults CHF 15

Students, trainees, seniors, people with disabilities CHF 10

Groups of 20 people or more CHF 10 (per person)

Children aged 16 or under: free